To celebrate Black History Month – and the vital contributions of Black, Afro-, and African American artists and musicians to American roots music – BGS, Good Country, and our friends at Real Roots Radio in southwestern Ohio have partnered once again. This time, we’ll be bringing you weekly collections of a variety of Black roots musicians who have been featured on Real Roots Radio’s airwaves. You can listen to Real Roots Radio online 24/7 or via their FREE app for smartphones or tablets. If you’re based in Ohio, tune in via 100.3 (Xenia, Dayton, Springfield), 106.7 (Wilmington), or 105.5 (Eaton).

American roots music – in any of its many forms – wouldn’t exist today without the culture, stories, skills, and experiences of Black folks. Each week throughout February, we’ll spotlight this simple yet profound fact by diving into the catalogs and careers of some of the most important figures in our genres. To kick us off, RRR host Daniel Mullins shares songs and stories of Big Al Downing, Yola, Cleve Francis, Charley Crockett, Elizabeth Cotten, Dom Flemons, and Lead Belly.

We’ll return each Friday through the end of the month to bring you even more music celebrating Black History and the songs and sounds we all hold dear. Plus, you can find a full playlist with more than 100 songs below from dozens and dozens of seminal artists, performers, songwriters, and instrumentalists from every corner of folk, country, bluegrass, old-time, blues, and beyond.

Black history is American roots music history; the two are inseparable. As we celebrate Black History Month and its legacy, we hope you’ll join us in holding up and appreciating the artists who make country, bluegrass, blues, folk, and Americana the incredible and impactful genres that they are today.

Big Al Downing (1940 – 2005)

Big Al Downing was an engaging entertainer whose winding career included forays into many genres, including country music. An Oklahoma boy, Downing played piano on Wanda Jackson’s signature rockabilly hit, “Let’s Have A Party,” before pursuing a solo career, finding some mainstream success, dabbling in R&B, and even scoring a Number 1 disco hit, “I’ll Be Holding On.”

However, Downing made history in country as one of the earliest Black artists to find success in the genre. Beginning in the late ’70s, he would have a string of fifteen singles hit the Billboard country charts over the next decade, three of which reached the Top 20. He was nominated by the Academy of Country Music for their Top New Male Vocalist award in 1980. Big Al would be a frequent guest on the Grand Ole Opry, Hee Haw, Nashville Now, and more.

Downing’s soulful singing on hardcore country songs like “Bring It On Home” and “Touch Me (I’ll Be Your Fool Once More)” endeared him to fans, while his story song “Mr. Jones” has remained beloved by country enthusiasts. His career spanned five different decades of country, rockabilly, and more, remaining active in the country music world until shortly before his passing in 2005 after a brief battle with leukemia. Downing is a member of the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame and Rockabilly Music Hall of Fame, and his legacy is still remembered by longtime fans of country music.

Suggested Listening:

“Mister Jones”

“Touch Me (I’ll Be Your Fool Once More)”

Yola (b. 1983)

Yola is a soul, country, and roots powerhouse! Born in the United Kingdom, Yola’s voice is a force of nature – rich, soulful, and packed with emotion. She started as a songwriter and backing vocalist before stepping into the spotlight with her 2019 debut album, the GRAMMY-nominated Walk Through Fire! Featuring contributions from Vince Gill, Molly Tuttle, Charlie McCoy, Ronnie McCoury, and more, the project was produced by Dan Auerbach of The Black Keys, and quickly endeared her to roots music lovers everywhere. She even appeared as a guest vocalist with all-star group The Highwomen.

With her unique blend of country, rock, and soul, Yola shatters boundaries. In 2021, she dropped Stand for Myself, an album full of bold, genre-blending anthems that brought her more GRAMMY noms. She has even dabbled in acting as of late, appearing on Broadway in Hadestown and playing Sister Rosetta Tharpe in the hit blockbuster Elvis. Do yourself a favor and check out this bon a fide star in roots music.

Suggested Listening:

“Whatever You Want”

“Hold On” (featuring Sheryl Crow, Brandi Carlile, & Natalie Hemby)

Cleve Francis (b. 1945)

Do you remember Cleve Francis? He grew up listening to Hank Williams in Louisiana as a child before making his first guitar out of window screen wire and a King Edwards Cigar Box on his way to becoming an inspiring country artist. Cleve isn’t just a singer – but he’s a songwriter, a dreamer, and a doctor? That’s right, before he hit the stage, Cleve was saving lives.

Dr. Cleve Francis was a practicing cardiologist before he pursued his passion for country music full-time in the late ’80s. Cleve brought a fresh voice to the genre in the 1990s with his smooth voice and heartfelt lyrics that resonated with country fans, resulting in four singles on the Billboard country charts. Cleve’s style of country earned him appearances on major stages like the Grand Ole Opry, The Today Show, and more.

Though he eventually returned to medicine, Francis left an enduring legacy, inspiring many Black country artists who have followed in his wake. He was instrumental in the curation of the Country Music Hall of Fame & Museum’s “From Where I Stand: The Black Experience in Country Music” exhibit while also helping found the Black Country Music Association in the mid ’90s.

In 2021, he was recognized with a Black Opry Icon Award, and his album Walkin’ is on display at the National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington D.C., where he could still been seen frequently performing at the legendary Birchmere music club until his retirement in 2021.

Suggested Listening:

“Love Light”

“You Do My Heart Good”

Charley Crockett (b. 1984)

One of the most authentic voices in modern American roots music, Charley Crockett has a story that sounds borderline mythical. A descendant of Davy Crockett who grew up in Texas, Crockett spent his early years busking on street corners from New Orleans to Dallas to New York, learning the art of storytelling from life itself. His travels took him to California, Paris, Spain, and Morocco before returning to Texas and releasing his debut album in 2015. Crockett’s recording output has been impressive, frequently releasing multiple albums a year and balancing his records with heartfelt originals and a deep catalog traditional songs from the likes of Tom T. Hall, Hank Williams, Willie Nelson, George Jones, Johnny Paycheck and more.

The common denominator is Charley – his voice carries a raw, timeless quality that cuts straight to the heart. Now performing at the Ryman Auditorium and on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, Charley’s rise hasn’t gone unnoticed. He’s earned critical acclaim and has racked up accolades from the American Music Association and a GRAMMY nomination. With black, Cajun, Creole and Jewish heritage, Crockett’s unique take on country and American roots music is sure to speak to music lovers everywhere for years to come.

Suggested Listening:

“Jukebox Charley”

“$10 Cowboy”

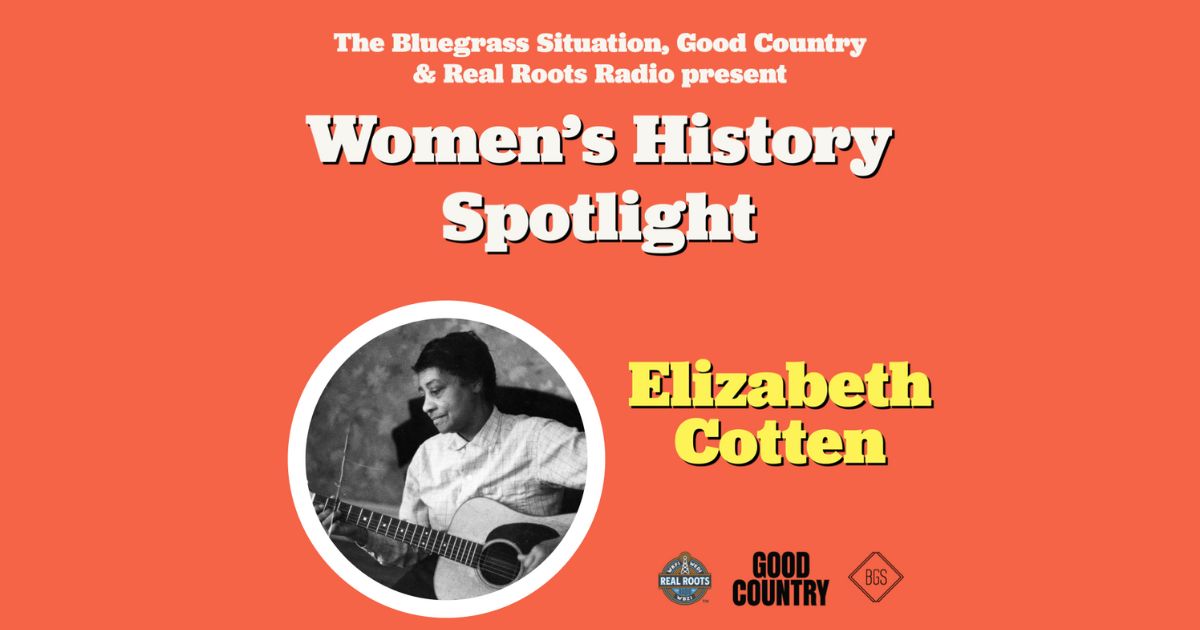

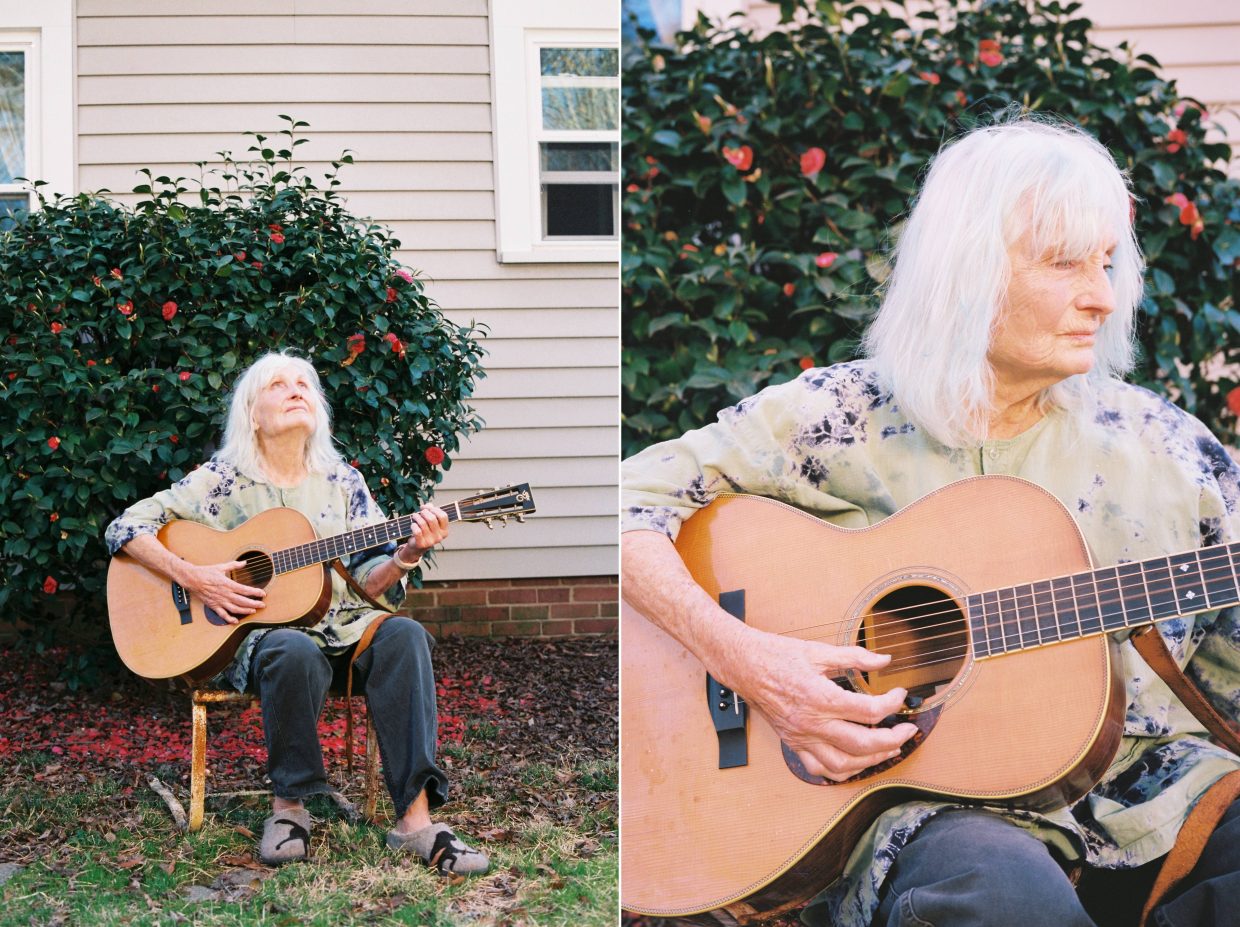

Elizabeth Cotten (1893 – 1987)

An underappreciated hero of American folk and blues, Elizabeth Cotten was born in 1893 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Growing up in a musical family, by the time she was 7 Elizabeth taught herself to play guitar left-handed. She flipped the guitar upside down, creating her own unique picking style, now known as “Cotten picking,” which featured alternating bass notes played with her fingers while her thumb played the melody.

Elizabeth wrote her iconic song, “Freight Train,” when she was just 12 years old. This classic has been recorded by Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Tommy Emmanuel, Doc Watson, and dozens more artists across multiple genres. But her music remained largely unheard for decades as she spent much of her life working as a domestic housekeeper. It wasn’t until she reached her 60s, while working for the Seeger family – yes, that Seeger family – that her incredible talent received a proper platform. Working for a family that loved and appreciated music inspired Elizabeth to resume playing. With the Seegers’ encouragement, Elizabeth recorded her first album, Folksongs and Instrumentals with Guitar, in 1958, recorded at home by Mike Seeger, a member of the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame.

Cotten went on to perform at major festivals thanks to the folk revival, w0n a GRAMMY at age 90, and inspired countless musicians before passing away in Syracuse, New York at the age of 94. Elizabeth Cotten was posthumously inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2022.

Suggested Listening:

“Shake Sugaree” [Live]

“Oh Babe, It Ain’t No Lie”

Dom Flemons (b. 1982)

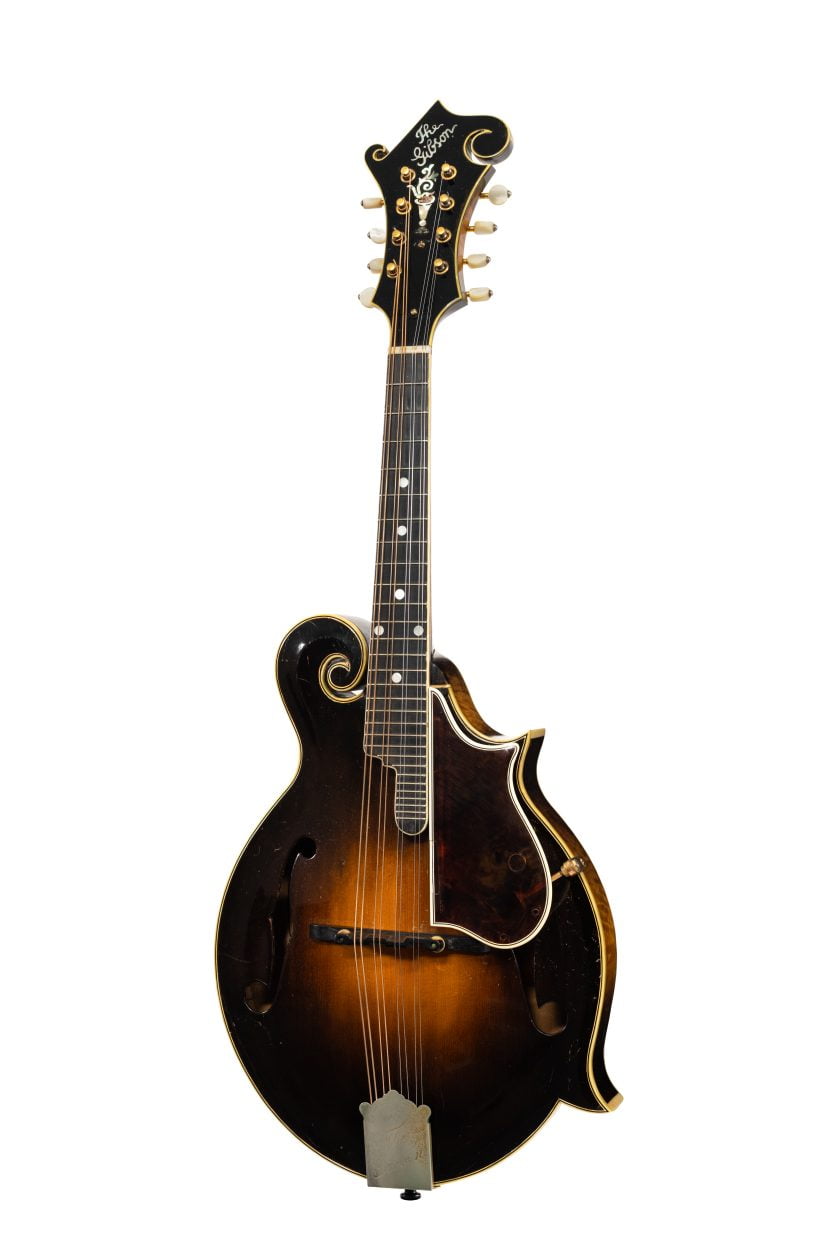

Let’s shine a spotlight on a modern-day troubadour, the Grammy-winning musician, historian, and storyteller Dom Flemons, The American Songster. An avid folk music fan, Flemons was a busker in his home state of Arizona before moving cross country to North Carolina to help found the Carolina Chocolate Drops, a band that revived the nearly forgotten legacy of Black string band music.

Flemons has been a successful solo artist for the last decade-plus. He is a master of multiple instruments – banjo, bones, guitar, harmonica – you name it! His music blends old-time, folk, blues, jazz, and country, tracing the deep roots of African American contributions to American music. From the Grand Ole Opry to Carnegie Hall, Flemons brings history to life with every note.

His 2018 album, Black Cowboys, uncovered the often overlooked stories of African American pioneers in the West, earning critical acclaim and a GRAMMY nomination. Today, whether performing solo or collaborating with legends like Taj Mahal, Sam Bush, and Rhiannon Giddens, Flemons keeps the rich traditions of American roots music alive. In addition to educating audiences about the origins of roots music, Flemons creates great original music as well, truly embodying his moniker.

As The Boston Globe said, “most folk artists go by ‘singer-songwriter’ or simply ‘musician.’ But ‘American Songster’ speaks to a greater truth about the work Flemons, a multi-instrumentalist, has accomplished.” We couldn’t agree more.

Suggested Listening:

“Steel Pony Blues”

“Nobody Wrote It Down”

Lead Belly (1888 – 1949)

He was a man of legend, his voice as powerful as the chains that once bound him. Born Huddie Ledbetter in 1888, the world knows him as Lead Belly. Imprisoned and pardoned multiple times, Lead Belly carried his music from the prison yards of Louisiana to the streets of New York City.

Legend has it that his musical gift led to his release. His background makes his prison, chain gang, and work songs even more haunting, including “Midnight Special.” His original song, “Goodnight Irene,” has been recorded more than two hundred times, including versions by Ernest Tubb & Red Foley, Moon Mullican, Frank Sinatra, Jerry Reed, and Johnny Cash. It is viewed as a verified country standard.

“Duncan and Brady,” “In the Pines,” “Cotton Fields” – his songs told stories of hardship, freedom, and the American experience. Lead Belly’s music shaped folk, blues, rock, and country inspiring legends like Creedence Clearwater Revival, Bob Dylan, Robert Plant & Alison Krauss, Pete Seeger, Johnny Cash, The Johnson Mountain Boys, and Nirvana.

Lead Belly died in 1949, but his music lives on. His voice still echoes in every blues riff and folk song today. Lead Belly was posthumously inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1988.

Suggested Listening:

“Black Girl (In The Pines)”

“Irene (Goodnight Irene)”

Want more Good Country? Sign up on Substack for our monthly email newsletter full of everything country.

Listen to Real Roots Radio online 24/7 or via their FREE app for smartphones or tablets.

Photo Credit: Big Al Downing via Team Entertainment Records; Elizabeth Cotten via Smithsonian Folkways Recordings; Yola by Valeria Rios.