At BGS, we seek out roots music from all corners — for those readers encountering us for the first time, we’re not “just bluegrass.” With our annual year-end list, we’ve shaken off the “best of” title and instead gathered 20 recordings that inspired our staff and contributors. For many reasons (but especially the long-awaited return of live music and festivals), we look ahead to 2021, but first… here are the albums and songs that inspired us in 2020.

Courtney Marie Andrews – Old Flowers

Courtney Marie Andrews couldn’t touch my heart deeper. Her music has been the healing salve for the wounds of 2020. To me, she’s the true definition of an artist: A songwriter, a musician, a painter, a writer, a singer, a poet, an activist. My favorite song on her magical 2020 album is “Old Flowers.” It’s the perfect metaphor of resilience and rebirth after suffering, both in love and in life. Becoming whole again. If that ain’t a theme we could all grow from this year, I don’t know what is! – Beth Behrs

Anjimile – “Maker (Acoustic)”

Anjimile’s Giver Taker was the album I can’t stop (and won’t stop) telling people about in 2020. The full version of their single, “Maker” was a beautiful amalgamation of cultures and influences synthesized by an artist not constrained by cultural and creative preconceptions. To me, Anjimile’s acoustic version of the lead single distills the brilliance of their songwriting into its purest form. – Amy Reitnouer Jacobs

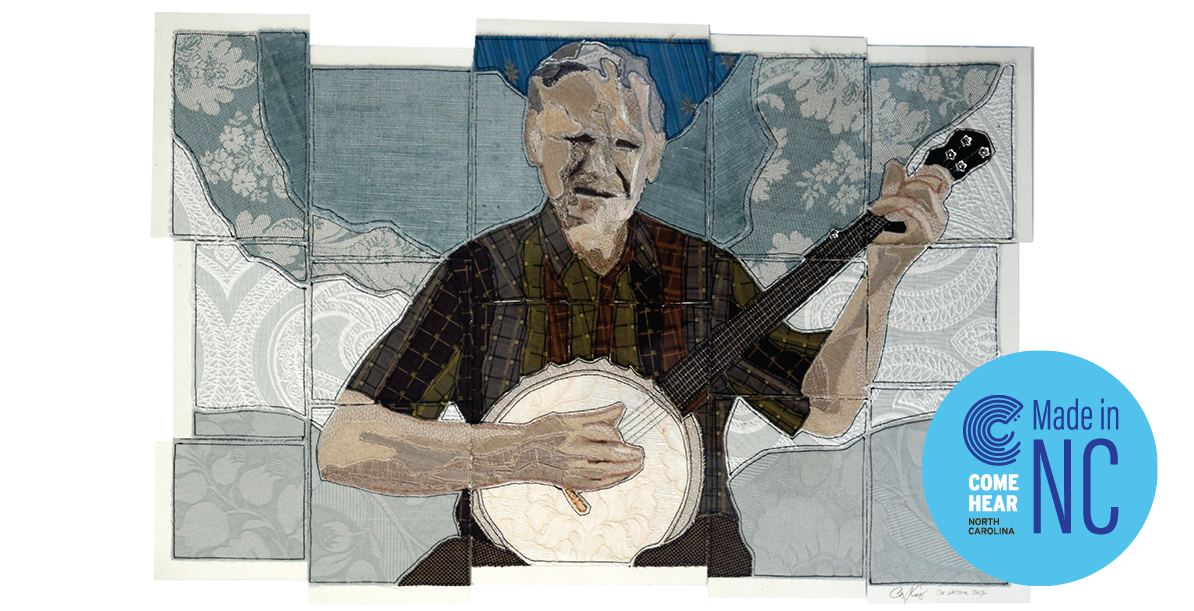

Danny Barnes – Man on Fire

Danny Barnes’ Man on Fire was a worthwhile gift to us all this year. Over the last couple of years, I’d heard chatter of a project in the works with names like Dave Matthews, John Paul Jones, and Bill Frisell involved. I am constantly in awe of what Barnes can create using the banjo as a pencil. This record was no exception, combining his unique style and songwriting with an electrified crew. – Thomas Cassell

Bonny Light Horseman – “The Roving”

There’s an odd bit of sorcery in the first measures of “The Roving,” a new version of an old folk tune on this supergroup’s debut. It opens tentatively, the instruments falling into the song like autumn leaves: First an acoustic guitar, then cymbals, then piano, all coalescing into a windblown arrangement that’s both understated and sublime. – Stephen Deusner

Bob Dylan – Rough and Rowdy Ways

Packed with jumbles of historic/cultural references and tall tales, bluesy swagger and prayerful romance, and climaxing with the shattered-mirror JFK assassination epic “Murder Most Foul,” Dylan’s first set of originals in a decade is breathtakingly masterful. It’s also, often, hilarious. Nearing 80, the Bard’s as playful as ever. And as poignant. And, justifiably, as cocky. – Steve Hochman

To me, Bob Dylan’s best era started in 1989 with his 26th studio album, Oh Mercy, and continues to this day with his 39th, Rough and Rowdy Ways. “Murder Most Foul” shows us that the master of his generation is as much in control of his folktale troubadour craft as he’s ever been. – Chris Jacobs

Justin Farren – Pretty Free

Knowing nothing about Justin Farren, I was immediately sucked into his evocatively detailed story-songs that involved returning diapers to Costco, getting a “two-paycheck ticket” while trying to impress a girl, and (in the all-too-appropriately-titled for-2020, “Last Year Was The Best Year”) a wild Disneyland adventure. Full of humor, sorrow, regrets and hope, Pretty Free was a musical world I visited often this year. – Michael Berick

Mickey Guyton – “Black Like Me”

Mickey Guyton’s lyrics illuminate the individuality and dilemma of any non-white vocalist in country music, and in particular the difficult journey of Black women in the field. Her performance is gripping and memorable, paying homage to many others who’ve faced ridicule and questions about why they’re daring to perform in an idiom many still feel isn’t suited for their musical style. – Ron Wynn

Sarah Jarosz – “Pay It No Mind”

Atop a Fleetwood Mac-style groove, Sarah Jarosz imagines the advice a distant bird might offer. But her songbird is no sweet, shallow lover. She comes with the weight and wisdom of something more timeless. Jarosz lets her fly via mandolin-fiddle interplay that personifies the tension between the endless sky and the “world on the ground.” – Kim Ruehl

Lydia Loveless – Daughter

“I’m not a liberated woman,” Lydia Loveless declares on her fifth album, “just a country bumpkin dilettante.” Don’t you believe it. Written in the shadow of her 2016 divorce and beautifully sung in a voice both epic and straightforward, Daughter finds this Americana siren at the height of her formidable powers. – David Menconi

Lori McKenna – The Balladeer

Lori McKenna‘s singular talent for capturing the joy in everyday details is on full display, from the church parking lots and hometown haunts of “This Town Is a Woman” to the stubborn tiffs and make-up kisses on “Good Fight.” But The Balladeer acknowledges the hard-as-hell times, too. With gentle accompaniment, commanding melodies, and McKenna’s signature lyrical wit, The Balladeer showcases a modern songwriting master. – Dacey Orr Sivewright

Jeff Picker – With the Bass in Mind

I love “new acoustic music,” but am often afraid I’ll be disappointed by it. Jeff Picker’s With the Bass in Mind immediately eases those worries by offering music that is creative, thoughtful, unexpected, and virtuosic while still feeling grounded and musical. All while effortlessly answering the once-rhetorical question: “What would a solo bluegrass bass album even sound like?” – Tristan Scroggins

William Prince – Reliever

William Prince‘s Reliever feels like the best pep talk I’ve ever had. In particular, “The Spark” finds him astonished with loving a partner who loves him back, no matter his own perceived flaws. As a whole, the album explores complicated emotions with a comforting arrangement (with duties shared by Dave Cobb and Scott Nolan). Sung with assurance by Prince, almost like he’s confiding in you, Reliever is both encouraging and excellent. – Craig Shelburne

Scott Prouty – Shaking Down the Acorns

We’d be remiss in our jobs as procurers of roots music culture to not include this stoically beautiful record on our year-end list of the very best. A hearty collection of 24 (mostly solo) old-time fiddle and banjo songs, there is something ever-present, comforting, and timeless about Prouty’s playing, and I have no doubt this is a record I’ll be revisiting like an old friend for years to come. – Amy Reitnouer Jacobs

Emily Rockarts – Little Flower

Montreal-based songwriter Emily Rockarts’ debut album Little Flower is one to remember. Produced by Franky Rousseau (Goat Rodeo Sessions), the album features lilting cinematic ballads punctuated with dance-in-your-room indie anthems. Rockarts’ musicianship is undeniable; her stunning melodies and refreshingly earnest lyrics make for a remarkable combination that is unlike anything else I’ve heard. Run, listen to Little Flower now! – Kaia Kater

Sarah Siskind – Modern Appalachia

Sarah Siskind brought her luminous, Nashville-honed songwriting back home to North Carolina a few years ago and let the mountains speak through her. Leading an all-star Asheville band live off the floor at iconic Echo Mountain studio, she’s made a heart-swelling set of songs that gather her special melodic signature, her meticulous craft, and her insight into how a rich musical region is evolving. – Craig Havighurst

Emma Swift – Blonde on the Tracks

Emma Swift reminded the music world of the power that artists have to control their work when she self-released Blonde on the Tracks, an eight-song collection of Bob Dylan covers. Her interpretations are as powerful and innovative as her methodical and thoughtful initial distribution sans streaming services. – Erin McAnally

Julian Taylor – The Ridge

Mohawk singer-songwriter Julian Taylor resides in what is now referred to as Toronto, but his masterful country-folk record, The Ridge, hits your ear as if plucked directly from Taylor’s childhood summers spent on his grandparents’ farm in rural British Columbia. Refracted through Taylor’s crisp, modern arrangements and undiluted emotion, The Ridge seamlessly bridges the elephant-in-the-2020-room chasm between rural and urban — musically, familially, lyrically, and spiritually. – Justin Hiltner

Molly Tuttle, “Standing on the Moon”

2020 has handed us its fair share of cover albums, with stay-at-home orders urging many to reach for the familiar — but none have meshed a variety of musical sources so creatively as Molly Tuttle’s whimsical …but i’d rather be with you. Her version of “Standing on the Moon” is the nostalgic and homesick, Earth-loving galactic trip of my pedal steel-obsessed, Deadhead dreams. – Shelby Williamson

Cory Wong – Trail Songs (Dawn)

A record that I didn’t know I needed came in early August when Vulfpeck guitarist Cory Wong released Trail Songs (Dawn). A change of pace for Wong, it features predominantly acoustic instrumentation and organic sounds. The album kicks off with “Trailhead,” which sounds like a Dan Crary instrumental until the groove drops in the second verse. BGS standbys Chris Thile and Sierra Hull make appearances as an added bonus. – Jonny Therrien

Donovan Woods – “Seeing Other People”

We may seem unsentimental, stoic, unemotional — especially when faced with something like a partner moving on, or a breakup, when it may be easier to seem fine, have a pint, and download Tinder. Donovan’s gift in this song is to show those complicated “yes, and” internal thoughts and emotions. It is beautiful. – Tom Power