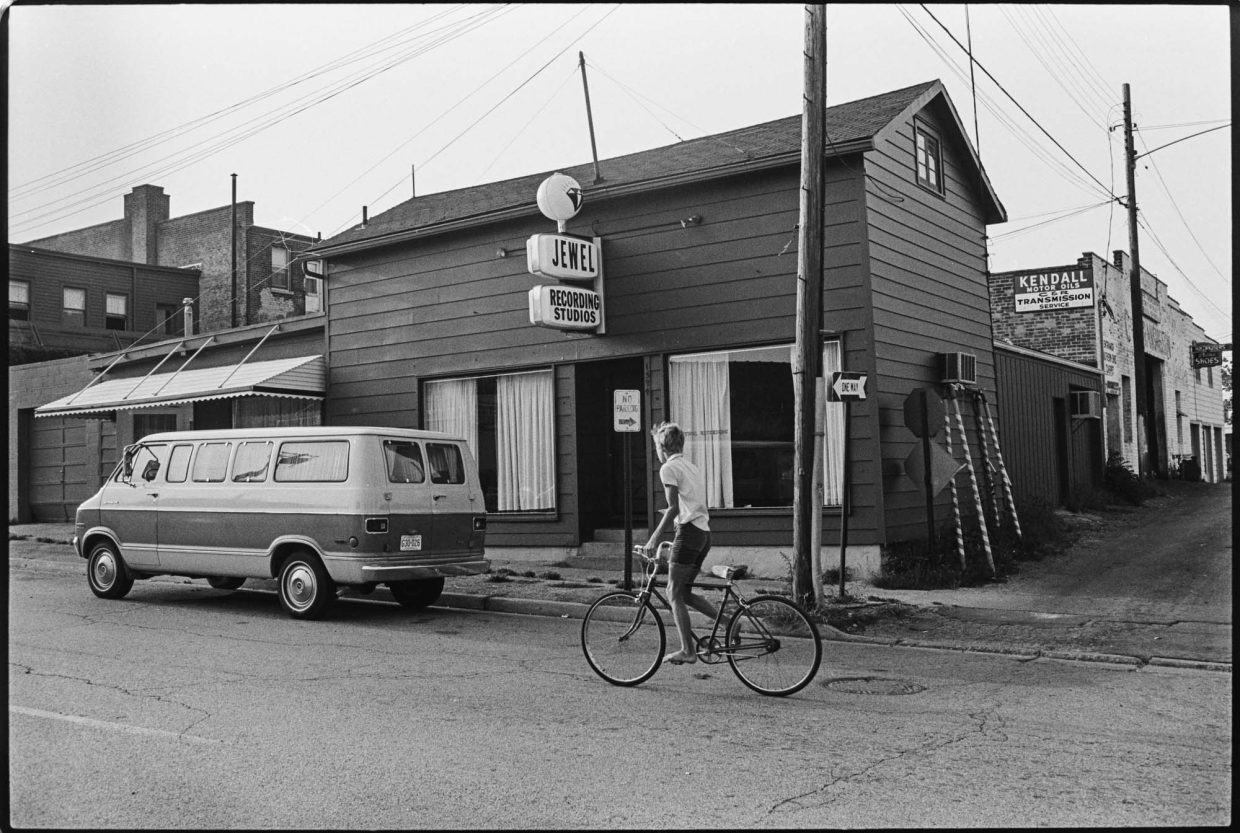

On the afternoon of Tuesday August 15, 1972, the day after Carl Fleischhauer and I interviewed J.D. Crowe in Lexington, Kentucky, we dropped in on Rusty York at his Jewel Recording Studios in Mt. Healthy, Ohio, a small city just north of Cincinnati.

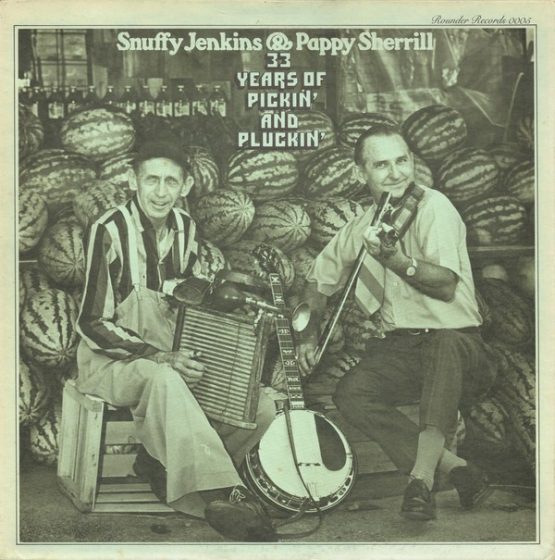

I first heard York in the fall of 1959 when Tom Barton, a new friend from Bloomington, Indiana, visited me in Oberlin and brought as a house gift a new LP by a company I’d never heard of, Starday. Banjo In The Hills (“16 Great Mountain Songs by All Star Artists 16”) included excellent numbers by bands I (a bluegrass fan since ’57) knew and liked: The Stanley Brothers, Carl Story, Bill Clifton, Jim Eanes, Jim & Jesse. It also included two tracks by a group new to me, Rusty York and Willard Hale: an instrumental, “Banjo Breakdown,” and a great cheating song, “Don’t Do It.”

I really took to that song! Our band Crooked Stovepipe put it on our first CD in 1993. We still do it at almost every show.

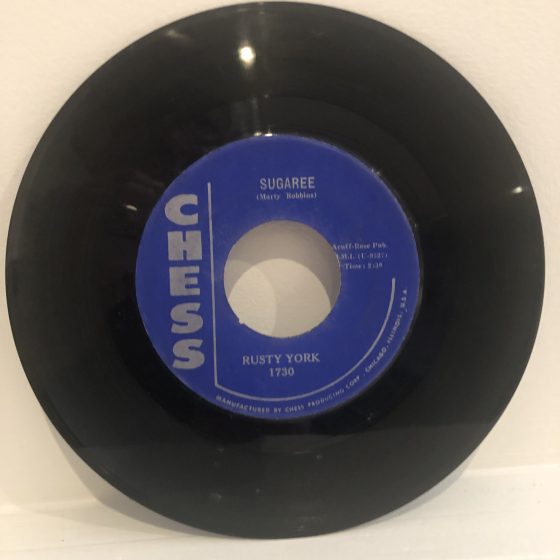

Keen to hear more of York and Hale, I added them to my mental checklist when shopping for recordings. At Oberlin, students couldn’t have cars, so we confined our shopping to a local shoe store’s sales bin of used jukebox 45s. Every once in a while, I’d snag recent singles by favorites like Monroe, Reno & Smiley, or Jimmy Reed. In 1960, not long after hearing “Don’t Do It,” I found “Sugaree,” a Chess Records single by Rusty York, in the bin. I hadn’t heard it, bought it on spec — the shoe store didn’t have a record player.

Man, was I disappointed when I got home and listened! It wasn’t bluegrass at all, it was a Marty Robbins rockabilly song, with York singing in a band fronted by sax and his electric guitar with piano, bass and drums behind:

The other side was “Red Rooster,” a rock version of “She’ll Be Comin’ Round the Mountain.” Not bad, some hot guitar licks, but pretty ho-hum, I thought. Must be a different Rusty York I figured; after all, Chess was a Chicago label, while Starday was from Nashville.

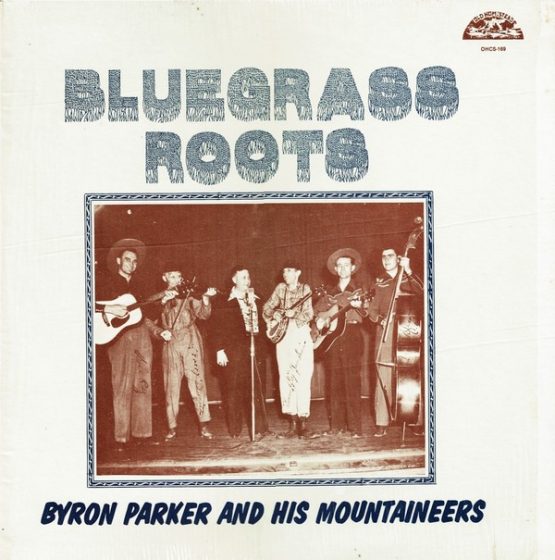

A couple years later in Bloomington, Indiana, I came across four EPs (45 rpm, big hole, six tracks each) by Rusty York and the Kentucky Mountain Boys on the Bluegrass Special label, distributed by Jimmie Skinner music in Cincinnati. What a contrast — bluegrass standards done up in proper style! The songs were all familiar bluegrass standards, like this version of the mountain folk song “Cindy”:

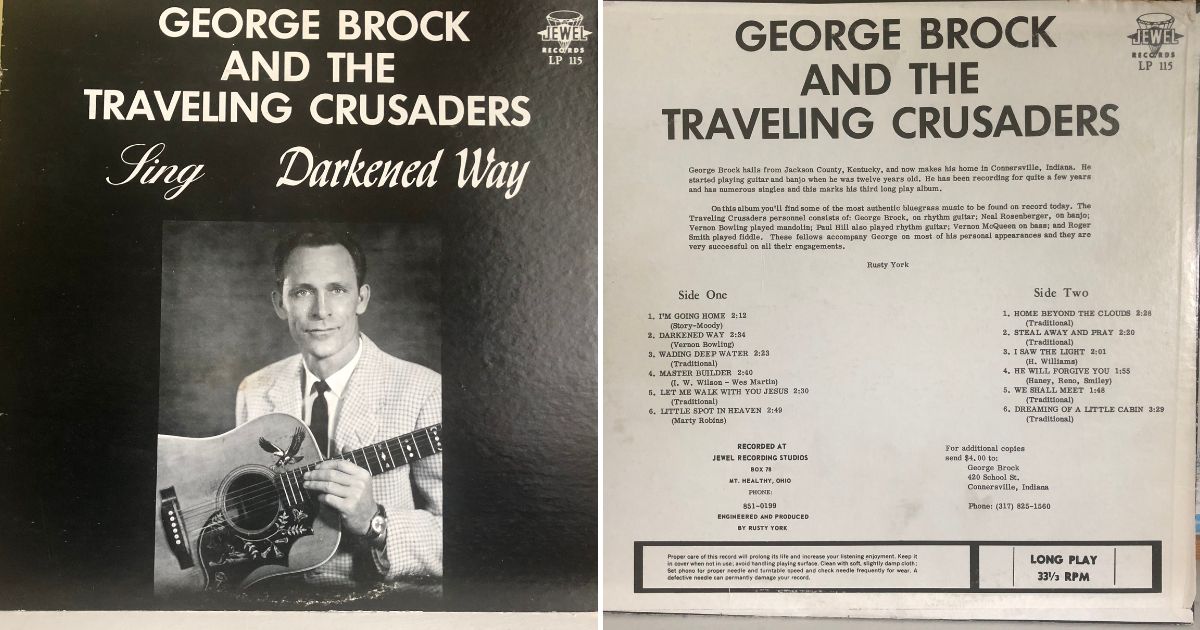

I didn’t hear of him again until the summer of 1967, when I was working in a southern Indiana band, the Stoney Lonesome Boys, led by fiddler Roger Smith. He was helping his friend George Brock, a Connersville-based gospel singer, put together an album and asked me if I would play banjo that fall on their recording at Rusty York’s studio in Ohio. Surprised to learn York had a studio, I accepted Roger’s invitation. We — Roger, Vernon McQueen, Vernon Bowling, Paul Hill, and I — rehearsed with Brock at Roger’s home in Columbus, Indiana, in September. On Sunday, October 1 we headed to the Cincinnati suburb of Mt. Healthy, Ohio. Accompanying us was bluegrass DJ Ervin Barrett.

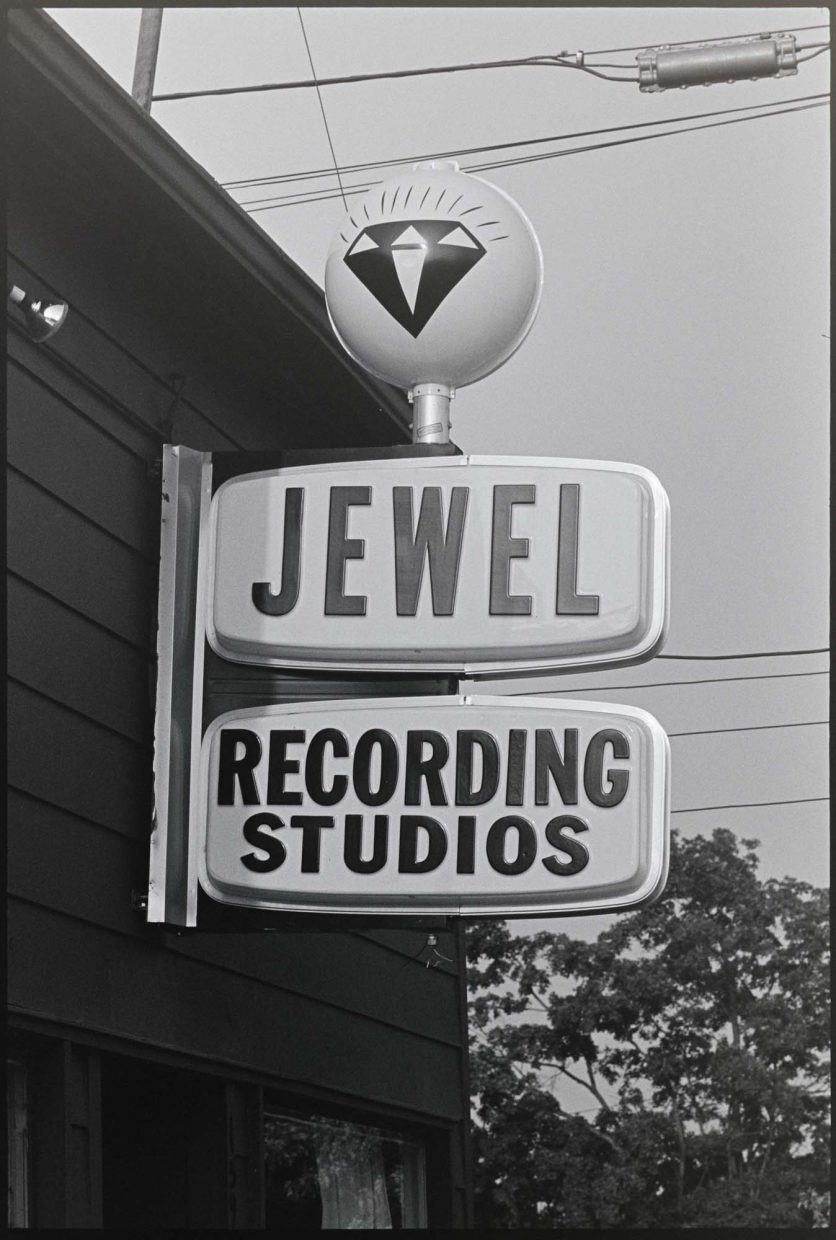

Rusty’s Jewel Recording Studio was a converted two-car garage attached to his suburban home. It was a big open room. Along the back wall was a raised glassed-in platform on which the recorder and mixing board sat. The recorder was a series 300 Ampex deck, an open reel machine just like the two in the studio of Indiana University’s Archives of Traditional Music where I was then employed. This state-of-the-art monaural unit recorded everything onto a single track.

Lines from 10 microphones fed into York’s mixing board. From them, through the board, emerged a single track that was fed onto the tape. We had six instruments and four voices. Each of us stood before one or two microphones. We could see and talk to each other over low baffles. Rusty had recorded bluegrass before. He had selected specific locations in the room for instruments and voices.

George Brock had chosen 12 songs. We were to record them in the sequence on which they would appear on the LP — beginning with side one, band one, and finishing with side two, band six. We tuned up, took our places in front of the mics, and started on the first song.

While we played, Rusty was at the mixing board setting levels. By the end of several run-throughs, he knew when the vocal trio came in or the mandolin took a break, how the song kicked off and ended, and other sonic arrangement features. Where the focus of the song moved from instruments to voices, he made mental notes to adjust the microphones at the right time. Each song had its moves, like running a football play or driving a race car for a lap.

He would tape each trial run through and play it back through big speakers. It soon became clear to me that York was very adept at mixing on the fly. We were there about three hours. About a month later George sent me a copy of the album, George Brock and The Traveling Crusaders, Jewel LP 115.

York’s brief notes give George’s bio, describe the album as “some of the most authentic bluegrass music to be found on record today,” identify The Traveling Crusaders personnel (I was “Neal Rosenberger”), and close by saying: “These fellows accompany George on most of his personal appearances and they are very successful on all their engagements.” I suppose we were successful at this, our only engagement! It’s one of my favorite recordings, reminding me of both Roger Smith‘s coaching and York’s skill and vision as a producer.

When Carl and I began to plan our 1972 trip I pulled out that five-year old George Brock album and found Jewel’s PO Box and phone numbers. Before I left St. John’s, Newfoundland, I wrote Rusty at that address, told him I was planning research in Ohio and asked for an interview.

We hit the road that Tuesday in August 1972 after lunch in Louisville, and headed for Cincinnati, about 100 miles northeast along the Ohio River. My notes:

Arrived in Mt. Healthy about 3:30 as I remember. Parked across the street from a phone booth, went to call Rusty York and as it turned out the number I had was out of date.

I looked up Jewel in the phone book and found the address was just around the corner from us.

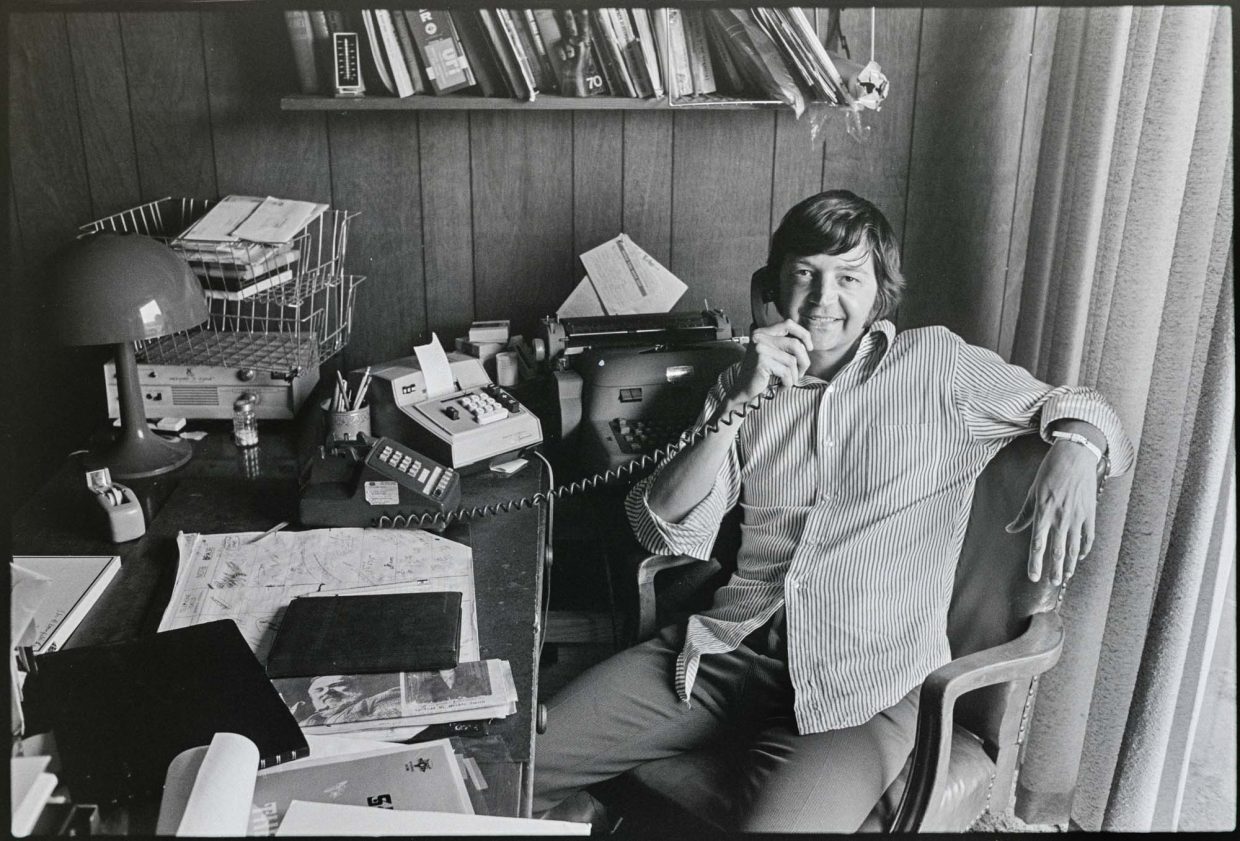

We walked over, went in. A number of people milling around, not looking surprised or impressed to see us — a secretary said Rusty was out to lunch and so I explained who we were and that I’d written, etc. She called him at home and then said he’d be back soon. When he returned, he was quite cordial, said he hadn’t had time to answer (I hadn’t expected him to), and he was booked solid with sessions and didn’t have time for an interview but if we wanted to stick around, we were welcome.

He immediately engaged Carl in conversation vis-à-vis cameras and such, pulled his cameras out of his safe, told of recording a gospel rock festival the previous weekend (a 4-track [recorder] along with other equipment, sat in a Dodge van outside the studio) at which there was a big movie outfit a la Woodstock — they used his sound. He takes all the cover photos, hence the interest in cameras.

Though I’d known some of the high points of Rusty’s career (the early bluegrass, the rockabilly hit, The Bluegrass Special EPs) and had worked in his studio, I really didn’t know much about him beyond that. Born in 1935, raised in Eastern Kentucky, he’d moved to Cincinnati when he was 17. By the 1972 he’d had a long career there as a performer and a worker in the music industry. His story is told online at Hillbilly-Music.com. A more detailed account was published by the late bluegrass and county historian Ivan Tribe’s July 1998 article in Bluegrass Unlimited.

By that August 1972 afternoon, Rusty had pretty much left behind the life of performing that developed during his 20 years in Cincinnati.

He moved into Cincinnati’s “Over The Rhine” Appalachian immigrant neighborhood in 1952. He was seventeen. He didn’t finish high school, going to work right away in a restaurant. He moved next to a job as an office boy in a stockbroker’s office. In the evenings he started going to the local music clubs. He was already playing guitar and banjo. Meeting other “briars” like Willard Hale, he played in local clubs and, as he would describe to us that afternoon, mixing rock and roll beside the bluegrass. He also began working in radio. He became a familiar figure in the regional country music business.

York soon became acquainted with another Kentuckian, the leading figure in the Cincinnati country scene, Jimmie Skinner, a hillbilly singer whose recording career began in the 1930s. By the mid-’50s his Jimmie Skinner Music Center was the leading mail-order country music business in the U.S. Rusty worked on Skinner’s weekly broadcasts from the Center as engineer, DJ, and musician; and he also played in Skinner’s band. Here’s what Rusty and Jimmie sounded like, later, in 1961, on Skinner’s most famous composition, “Doin’ My Time.”

York next ventured into recording. His first sides were covers of new rock and roll hits, including a Buddy Holly tune released in 1957 on Syd Nathan’s King records. His next recordings were made the following year accompanying Kentucky-born country singer, also a Skinner employee, Connie Hall, on Mercury-Starday, and it was at this time he cut his first bluegrass sides with Hale, including “Don’t Do It.”

By 1959 York was again recording rockabilly covers, and it was in this context that “Sugaree” came about. This was his only hit, and it led to a tour sponsored by Dick Clark that began at the Hollywood Bowl where Rusty opened for a show that included Annette Funicello, Duane Eddy, and Frankie Avalon.

Rusty made further rock singles and was later inducted into the Rockabilly Hall of Fame. Although he made a few appearances with this music in rockabilly nostalgia tours, his musical career after “Sugaree” moved in the direction of country and folk.

In 1961 he returned to bluegrass, producing the Bluegrass Special EP series mentioned earlier. At this point he started his own studio. Then, in 1964 and 1965, he began a stint as the opening act for Bobby Bare.

Bare – who grew up in Ironton, Ohio, southeast of Cincinnati, just across the river from Kentucky and West Virginia – began his career in Southern Ohio, but by the time Rusty joined his operation he was a national country star, a Grammy winner with hits like “Detroit City.” Here’s what Bare’s show looked like around time Rusty joined him:

Rusty made some country recordings during his tours with Bare, which included numerous stints in Las Vegas. By 1970 he’d scaled back his performing and focused more on the studio, and in fact now owned two studios.

To be continued. Next time, Hanging Out At Jewel…

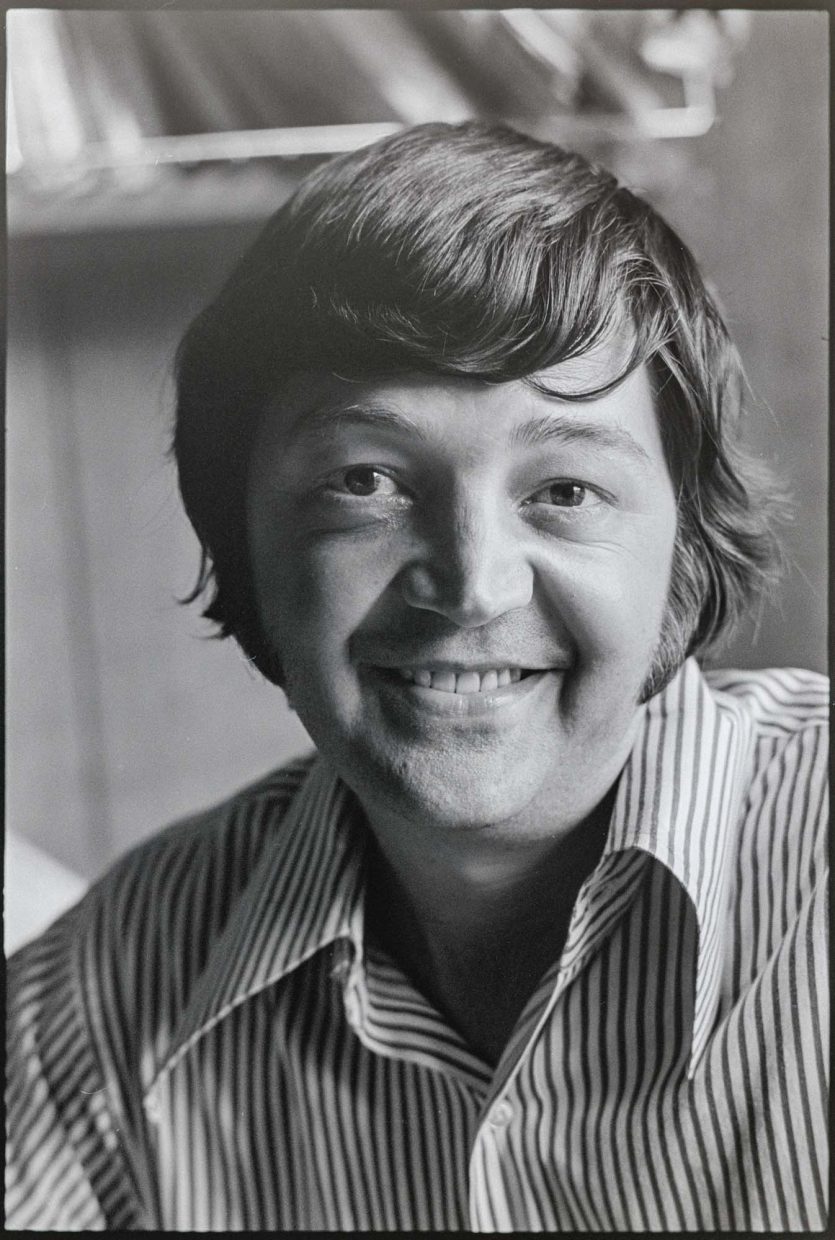

Neil V. Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, and co-chair of the IBMA Foundation’s Arnold Shultz Fund.

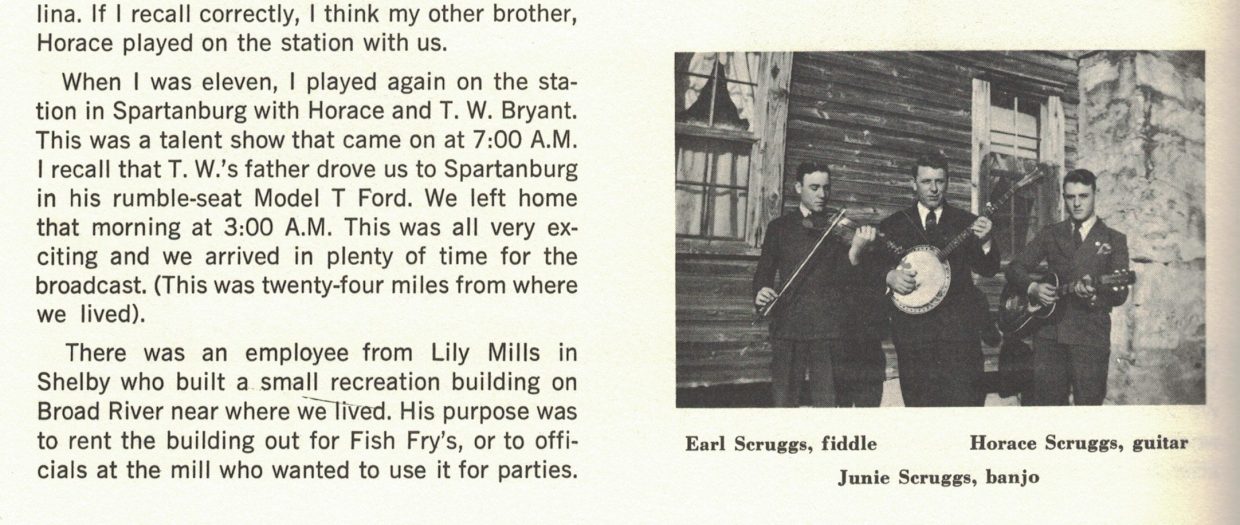

Photo of Rosenberg by Terri Thomson Rosenberg. Black and white photos by Carl Fleischhauer. Record photos by Neil V. Rosenberg.

Edited by Justin Hiltner.