While every country star knows how to tell a good story, it takes a particular strain of excellence to also be able to write one.

Songwriting is the gravitational center around which Good Country orbits. Lyrics that strike at the oceanic spread of human existence, chords that evoke its sprawling underbelly – the songwriter weaves both words and notes together, using each as a tool to explore the other.

Uniquely attuned to the value in lyrical narrative and authenticity, country music self-selects its fair share of multi-hyphenate talents who, beyond their performative prowess or instrumental skills, have a knack for setting pen to paper. From Willie Nelson to Kacey Musgraves, country carries an extensive lineage of talented songsmiths. The following collection merely scrapes the surface of the best country star songwriters. Unsurprisingly, this list is a tangled web with many superb songwriters covering, popularizing, and collaborating on one another’s songs in true communal country fashion.

Willie Nelson

With over 300 songwriting credits to his name, Willie Nelson is indubitably one of the most prolific songwriters of all time – not just in country. Having written his first poem at the age of six, Nelson has nearly nine decades of steadfast dedication to the craft under his belt. Patsy Cline’s 1961 recording of “Crazy” lifted his songwriting further into the limelight. His pen went on to produce such potency that it helped define an entire new subgenre in the ‘70s— “outlaw country.”

Prized for his rebellious and forthright lyrical attitude, Nelson values raw emotion over placative commercial appeal, ironically earning him one of the most successful careers in country history. Over the years, Nelson has delivered a seemingly endless stream of hits performed by both himself and countless other musical giants, including Loretta Lynn, Merle Haggard, and Dolly Parton, just to name a few.

Bobbie Gentry

Bobbie Gentry is the keeper of a robust legacy of composing and performing. Having written her first song at age 7, Gentry taught herself to play a slew of instruments throughout her youth. When she attended college at UCLA, she began performing her songs out at the occasional nightclub, signing to Capitol Records some years later as an aspiring songwriter. In 1967, Capitol Records released “Ode to Billie Joe,” a song that Gentry had written and recorded herself. Gentry told The Washington Post that despite wanting to write songs for other artists, she only sang “Ode to Billie Joe” herself because it was cheaper than hiring another singer.

Despite her previous obscurity and the song’s dark tenor, “Ode” crept up the charts, surpassing the likes of Aretha Franklin and The Doors until it eventually pushed “All You Need is Love” out of the No. 1 spot. This astronomical success marked only the beginning of an industrious career for Gentry; she would go on to write and perform several other smash hits in addition to becoming the first woman to host a variety show on the BBC. She would later produce, choreograph, and write the music for her own nightclub revue in Las Vegas prior to retiring from show business.

Roger Miller

The King of the Road had range! Roger Miller’s songwriting legacy entailed chart-topping hits he wrote and performed himself, such as (of course) “King of the Road,” “Dang Me,” and “England Swings,” in addition to many that he wrote for other artists, such as “Billy Bayou” for Jim Reeves and Ray Price’s “Invitation to the Blues.”

His imaginative impulse made him uniquely qualified for the projects he took on later in life, including writing the music and lyrics for several songs in the 1973 animated Disney film Robin Hood, in which he also voiced Alan-a-Dale, the film’s rooster narrator. His acting career was even furthered by another musical project – Miller wrote the entire score for Big River, a Broadway musical based on Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. The musical premiered in 1985 and earned a total of seven Tony Awards, including Best Score. Miller even played the part of Pap (Huck Finn’s father) onstage for three months following the original cast member’s departure for Hollywood.

Kacey Musgraves

One of the most influential women in today’s country sphere, Kacey Musgraves has sculpted a name for herself for both her instrumental/vocal prowess and her impactful songwriting capabilities. Her solo catalog is chock-full of compelling songs that explore the “nuances of being a human, alive and experiencing consciousness,” as she told The Cut. The thoughtful universality of her songwriting has attracted a distinguished array of performers, with Musgraves contributing her skills to songs performed and recorded by Martina McBride, Miranda Lambert, and Deana Carter, among others.

Kris Kristofferson

This September marked a year since his passing, but Kris Kristofferson’s legacy continues to burn bright. His songs maintain a rugged, raw quality without sacrificing any of their vibrance. Though Kristofferson only landed one No. 1 hit on Billboard’s Hot Country Songs chart performing his own original material, his songs were platformed by many others featured on this list, including “Help Me Through the Night,” which Sammi Smith, Loretta Lynn and Willie Nelson recorded, and “For the Good Times,” a tune made famous by Ray Price that was later recorded by Dolly Parton, Merle Haggard, Willie Nelson, and more. Kristofferson also penned a fair number of tunes for The Highwaymen, the country supergroup composed of Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Johnny Cash, and Kristofferson himself, including their titular hit, “Highwayman.”

Trisha Yearwood

Author, singer, chef, Food Network television show host – just when we thought Trisha Yearwood had done it all, her 16th studio album, The Mirror, arrived this past July to showcase yet another talent you may not know that she held all along: songwriting. In an interview with Billboard, Yearwood recounts that discouragement during her college years largely held her back from incorporating songwriting into her career over the past three-plus decades. “It made me think I wasn’t a songwriter and I just always downplayed it,” she says.

The Mirror boasts powerful co-writes with many songwriters who’ve contributed to Yearwood’s earlier albums, including Rebecca Lynn Howard (“I Don’t Paint Myself into Corners”) and Maia Sharp (“Standing Out in a Crowd”). Of homing in on her songwriting craft, Yearwood shares, “It was really something that clicked a couple of years ago. I started writing and it was really kind of therapeutic and really evolved naturally out of something I felt like I needed to do and I’m so happy with how it came out.”

Merle Haggard

Widely recognized as one of the most legendary singer-songwriters of the country canon, Merle Haggard was a staunch believer in writing from his own experiences – of which he had many worth writing about. After losing his father at age nine, Haggard wound up in all sorts of trouble, from several stints in juvenile detention to developing a strong hitchhiking and train hopping habit. His rambunctious tendencies followed him into adulthood and eventually landed him in prison after an attempted robbery and subsequent failed jailbreak.

In 1960, Haggard’s life changed forever upon attending a Johnny Cash concert while incarcerated at San Quentin State Prison, which deeply inspired him. Upon his release later that year, Haggard set out to forge his own country career, garnering unspeakable success. From “Workin’ Man’s Blues” (co-written with Roy Edward Burris) to “The Bottle Let Me Down,” many of Haggard’s songs have become perennial classics.

Jimmy Buffett

Of all the narrative-focused songwriters, Jimmy Buffet undoubtedly took the premise of “world-building” the most literally. “Margaritaville,” the hit song which Buffett claimed took him only six minutes to write, has a transcendent legacy. From hotels to casinos to Broadway musicals, Buffett’s profoundly popular songwriting grew an empire. Of course, “Margaritaville” was certainly neither the beginning nor the end of Buffett’s extensive songwriting career; having released 30 albums (8 of which are certified gold and 9 of which are certified platinum or multi-platinum by the RIAA), Buffett was credited on upwards of 350 songs over the course of his life.

Don Gibson

Responsible for the songwriting behind some of the most famous songs in country history, Shelby, North Carolina, native Don Gibson was such a force that he, in fact, penned two of his most influential songs in the same day. “Oh Lonesome Me” and “I Can’t Stop Loving You” – which would go on to be recorded over 700 times by other artists including Ray Charles, Kitty Wells, and Loretta Lynn – were both conceived in a trailer park north of Knoxville, Tennessee, in 1957.

Bonnie Raitt

In addition to being the utter powerhouse musician that she is, Bonnie Raitt also knows her way around some lyrics. Having written most of her own music and with artists like Stevie Nicks and The Chicks covering her songs, Raitt’s songwriting has left an indelible mark on the blues, country, and Americana scenes. She’s known for her thoughtful and emotionally dynamic posture; for instance, her song “Down the Road” was inspired by a New York Times article Raitt read about a prison hospice program. Another, “Just Like That,” earned her a GRAMMY for Song of the Year and was inspired by a news segment featuring two families experiencing either end of an organ donation. Written from heartful depths, Raitt’s lyrics are both inspired and inspiring.

Cam

Best-known for her Grammy-nominated 2015 hit, “Burning House,” Cam (AKA Camaron Ochs) is one of the most prominent songwriters in the contemporary country scene. Another star and composer, in addition to her own four studio albums, Cam has writing credits featured on work from some of the largest industry giants in any genres. She has composed material for artists from Sam Smith to Miley Cyrus and 2024 saw her songwriting, backing vocals, and production lending a hand in several songs off of Beyonce’s chart-topping, culture-shifting country release, Cowboy Carter.

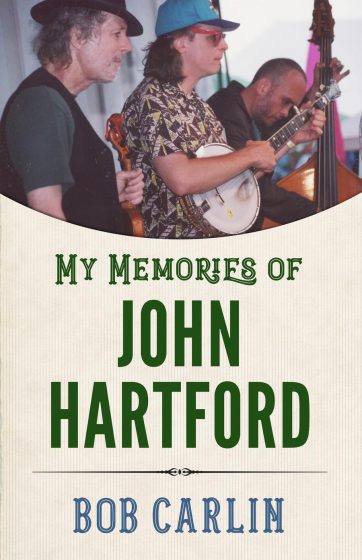

John Hartford

John Hartford’s talents truly knew no bounds. In addition to his multi-instrumental expertise, he was a fleet-footed clogger who could tear up a rug while he played. And he sure did know how to write a song. His most successful songwriting credit, “Gentle on My Mind,” (popularized by Glen Campbell and henceforth covered over and over again) earned him three GRAMMY awards and a listing among BMI’s Top 100 Songs of the Century. With covers from folks like Loretta Lynn, Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, Merle Haggard, and many more, it’s safe to say Hartford was one of the most respected – and most recorded and most covered – roots songwriters of his time. And of our time, too, as evidenced by this I’m With Her performance of “Long Hot Summer Days,” a Hartford original fiddler Sara Watkins once recorded on her own solo project.

Chris Stapleton

A fav of Good Country and our audience alike, Chris Stapleton has had a tremendously successful performing career in both bluegrass (via The SteelDrivers) and country (as a solo artist). His guitar prowess and smoky vocals aren’t his only claims to fame; even before his rise to stardom, Stapleton had written songs for some of the most commercially successful names in country and beyond. He’s been the pen-power behind songs for industry giants such as Luke Bryan, Kenny Chesney, Darius Rucker, George Strait, Lee Ann Womack, and more. Adele even recognized the potency of Stapleton’s powers back in 2011, having recorded a version of his smash hit SteelDrivers song “If It Hadn’t Been for Love” on a deluxe version of her album 21.

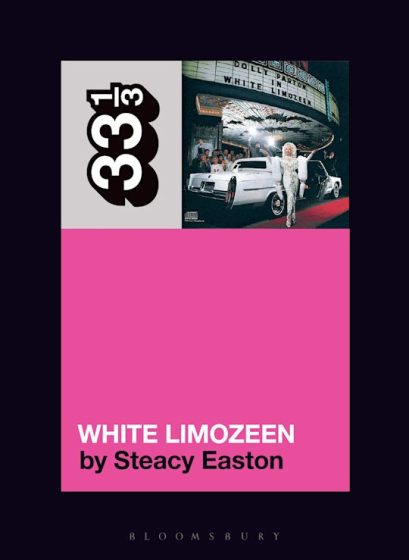

Dolly Parton

They don’t call Dolly Parton the queen of country for nothing! Illustrious and industrious, Parton estimates that she’s composed nearly 3,000 songs in her lifetime, with somewhere around 450 of them recorded. Her ability to world-build through dynamic characters and narratives has set the modern country standard for story-songs, with “Coat of Many Colors,” “9 to 5,” and, of course, “Jolene” being just some of her most chart-topping successes. She’s also written plenty for other artists – think Merle Haggard, Kenny Rodgers, Hank Williams Jr., Waylon Jennings, Emmylou Harris, and Tina Turner, just to name a few. And of course, we’d be remiss not to mention that Parton penned the biggest hit of Whitney Houston’s career!

Darrell Scott

In 2007 Darrell Scott was named the Americana Music Association’s Songwriter of the Year, and this year, 2025, he received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the organization, too. In short, Darrell Scott is a songwriting powerhouse – in addition to his status as one of Nashville’s premiere session musicians.

Similarly to many other artists on this list, albeit with his own stylistic flares, Scott champions the narrative song, writing tunes full of dynamic characters and story arcs that mesmerize. Outside of his own successful solo work, songwriting for others is the bedrock of Scott’s career. Among countless other contributions, Scott wrote the Chicks’ “Long Time Gone” (later to be sampled in Beyoncé’s “Daddy Lessons”), Travis Tritt’s hit song, “It’s a Great Day to Be Alive,” and the ever-relevant “You’ll Never Leave Harlan Alive,” which has been covered by Patty Loveless, Brad Paisley, Chris Stapleton, Kathy Mattea, Luke Combs, and many more.

Want more Good Country? Sign up to receive our monthly email newsletter – and much more music! – direct to your inbox.

Photo Credit: Kelly Christine Sutton