Ah! There’s a chill in the air, color in the leaves, and a craving for the spookiest songs in bluegrass — it must be fall. Bluegrass, old-time, and country do unsettling music remarkably well, from ancient folk lyrics of love gone wrong to ghost stories to truly “WTF??” moments. If you’re a fan of pumpkins, hot cider, and murder ballads we’ve crafted this list of 13 spooky-season bluegrass songs just for you:

The Country Gentlemen – “Bringing Mary Home”

THE bluegrass ghost story song. THE archetypical example of “What’s that story, stranger? Well, wait ‘til you hear this wild twist…” in country songwriting. (Yes, that’s a country songwriting archetype.) The Country Gentlemen did quiet, ambling — and spooky — bangers better than anybody else in bluegrass.

Cherryholmes – “Red Satin Dress”

Fans of now-retired family band Cherryholmes will know how rare it was for father and bassist Jere to step up to the microphone to sing lead. His grumbling, coarse voice and deadpan delivery do this modern murder ballad justice and then some.

One has to wonder, though, with so many songs about murderous, deceitful women in bluegrass — the overwhelmingly male songwriters across the genre’s history couldn’t be bitter and misogynist, could they? Could they?

Zach & Maggie – “Double Grave”

A more recent example of unsettling songwriting in bluegrass and Americana, husband-and-wife duo Zach & Maggie White give a whimsical, joyful bent to their decidedly creepy song “Double Grave” in the 2019 music video for the track. Just enough of the story is left up to the imagination of the listener. Feel free to color inside — or outside — of the lines as you decide just how the song’s couple landed in their double grave.

Alison Krauss – “Ghost in This House”

Come for the iconic AKUS track, stay for the impeccable introduction by Alison. Equal parts cheesy and stunning, if you haven’t belted along to this song at hundreds of decibels while no one is watching, you’re lying. Not technically a ghost story, we’re sliding in this hit purely because a Nashville hook as good as this deserves mention in a spooky-themed playlist.

The Stanley Brothers – “Little Glass of Wine”

Ah, American folk music, a tradition that *checks notes* celebrates the infinity-spanning, universe-halting power of love by valorizing murdering objects of that love. Kinda makes you think, doesn’t it? Here’s a tried and true old lyric, offered by the Stanley Brothers in that brother-duet-story-song style that’s unique to bluegrass. What’s more scary than an accidental (on purpose) double poisoning? The Stanley Brothers might accomplish spooky ‘grass better than any other bluegrass act across the decades.

Missy Raines – “Blackest Crow”

A less traditional rendering of a folk canon lyric, Missy Raines’ “Blackest Crow” might not feel particularly terrifying in and of itself, but the dark imagery of crows, ravens, and their relatives will always be a spectre in folk music, if not especially in bluegrass.

Bill Monroe – “Body and Soul”

The lonesome longing dirge of a flat-seven chord might be the spookiest sound in bluegrass, from “Wheel Hoss” to “Old Joe Clark” to “Body and Soul.” A love song written through a morbid and mortal lens, you can almost feel the distance between the object’s body and soul widening as the singer — in the Big Mon’s unflappable tenor — objectifies his love, perhaps not realizing the cold, unfeeling quality of his actions. It’s a paradox distilled impossibly perfectly into song.

Rhiannon Giddens – “O Death”

Most fans of roots music know “O Death” from the O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack and the version popularized by Ralph Stanley and the Stanley Brothers. On a recent album, Rhiannon Giddens and Francesco Turrisi reprise the popular song based on a different source — Bessie Jones of the Georgia Sea Island Singers.

The striking aural image of Stanley singing the song, a capella, in the film and on the Down from the Mountain tour will remain forever indelible, but Giddens’ version calls back to the lyrics’ timelessness outside of the Coen Brothers’ or bluegrass universes and reminds us of just how much of American music and culture are entirely thanks to the contributions of Black folks.

Johnson Mountain Boys – “Dream of a Miner’s Child”

Mining songs are some of the creepiest and most heartbreaking — and back-breaking — songs in bluegrass, but this classic performance from the Johnson Mountain Boys featuring soaring, heart-stopping vocals by Dudley Connell, casts the format in an even more blood-chilling light: Through the eyes of a prophetic, tragic dream of a miner’s child. The entire schoolhouse performance by the Johnson Mountain Boys won’t ever be forgotten, and rightly so, but this specific song might be the best of the long-acclaimed At the Old Schoolhouse album.

Oh daddy, don’t go to the mine today / for dreams have so often come true…

Emmylou Harris, Alison Krauss, Gillian Welch – “Didn’t Leave Nobody But the Baby”

A lullaby meets a field holler song on another oft-remembered track from O Brother, Where Art Thou? The disaffected tone of the speaker, in regards to the baby, the devil, all of the above, isn’t horrifying per se, but the sing-songy melody coupled with the dark-tinged lyric are just unsettling enough, with the rote-like repetition further impressing the slightly spooky tone. It’s objectively beautiful and aesthetic, but not… quite… right… Perhaps because any trio involving the devil would have to be not quite right?

AJ Lee & Blue Summit – “Monongah Mine”

Another mining tale, this one based on a true — and terrifying — story of the Monongah Mine disaster in 1907, which is often regarded as the most dangerous and devastating mine accident in this country’s history. AJ Lee & Blue Summit bring a conviction to the song that might bely their originating in California, because they make this West Virginia tale their own.

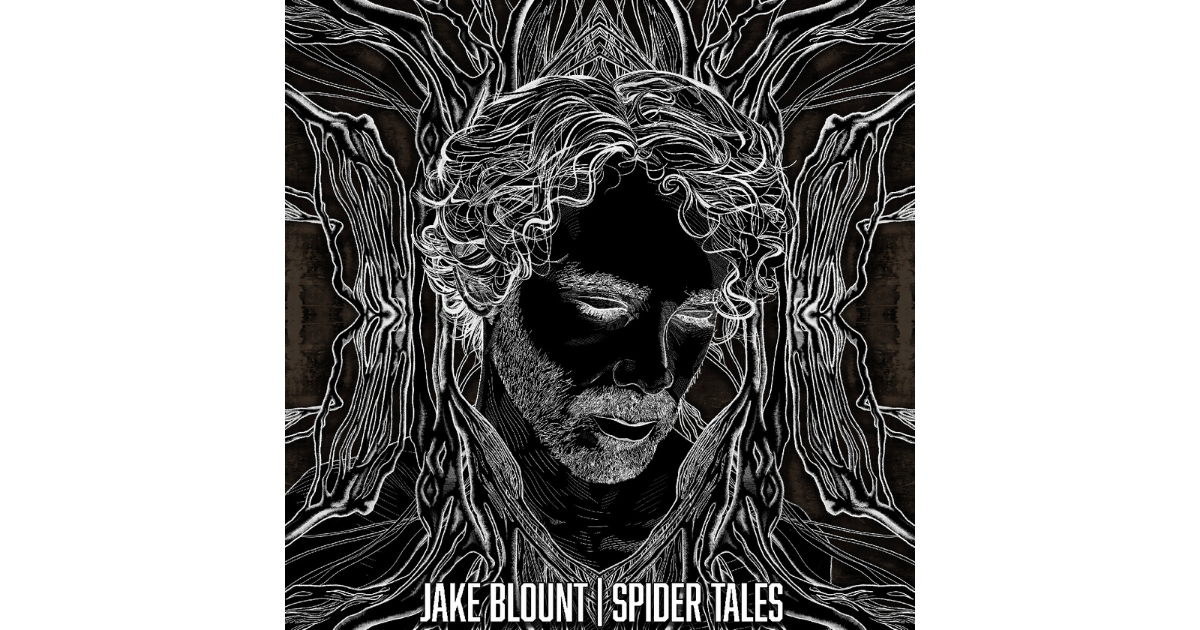

Jake Blount – “Where Did You Sleep Last Night”

“In the Pines” is one of the most haunting lyrics in the bluegrass lexicon, but ethnomusicologist, researcher, and musician Jake Blount didn’t source his version from bluegrass at all — but from Nirvana. That’s just one facet of Blount’s rendition, which effortlessly queers the original stanzas and adds a degree of disquieting patina that’s often absent from more tired or well-traveled covers of the song. A reworking of a traditional track that leans into the moroseness underpinning it.

The Stanley Brothers – “Rank Stranger”

To close, we’ll return to the Stanley Brothers for an often-covered, much-requested stalwart of the bluegrass canon that is deceptively terrifying on closer inspection. Just who are these rank strangers that the singer finds in their hometown? Where did they come from? Why do none of them know who this person or their people are? Why are none of these questions seemingly important to anyone? Even the singer himself seems less than surprised by finding an entire village of strangers where familiar faces used to be.

For a song so commonly sung, and typically in religious or gospel contexts or with overarchingly positive connotations, it’s a literal nightmare scenario. Like a bluegrass Black Mirror episode without any sort of satisfying conclusion. What did they find? “I found they were all rank strangers to me.” Great, so we’re right back where we started. Spooky.